Pat describes himself as a young Black entrepreneur, and says he aligns with an "old school Harlem."

Pat stands outside of a nail salon in Harlem.

“That saying, ‘it takes a village to raise a child?’ Well. That’s out the window in Harlem.”

by morgan young

Harlem Mothers Save is located on W 128th St. The organization, which aims to prevent gun violence - SAVE stands for "stop another unfortunate end," is run by Jackie Rowe-Adams, who is, according to one of her co-workers, "the heart of this organization." Unfortunately, Rowe-Adams' cause is never ending, and with senseless gun violence occurring from coast to coast, in 'hoods and universities, she is a hard woman to get a hold of. Her cause is noble, and her story, her pain, is unbelievable. Rowe-Adams lost both of her children to gun violence. In February 1982, her 17 year old son Anthony was murdered at 123rd St. by two men who thought that Anthony had been "staring at them." Her eldest son, Tyrone, was 28 when he was shot and killed by a 13 year old during a robbery outside of his apartment.

"The community is not like it should be, like it used to be. Like that saying, 'it takes a village to raise a child,'" mused a lifelong Harlem resident who introduced himself at Pat, "well. That's out the window." Pat said he aligned with an "old-school Harlem." One that saw more success and supported its residents. "This is not a healthy life. This is an area where you have to have a hundred thousand police around, twenty-four hours. They are needed, but when it's like this, it's not good. When you feel their presence around."

These things happen, but how? And if they are so common, why were Harlem residents of 129th street - one block away from Harlem Mothers Save, and six blocks away from the bodega where Anthony Rowe-Adams was murdered, so tight lipped? Was it an effort to protect themselves? To protect their community? Maybe Harlem's secrets, it's dirty laundry, is the kind of dirty laundry, that one has to be a Harlemite to learn about.

by Raissa Kouegbe

Sonny, 35, has been a victim of gun violence at the hands of the police.

When It comes to gun violence, there are many things that Americans are dealing with. Guns are part of a system that has been in place for so long. Gun Violence is a culture, and the right to bear arms is a law indicted through the Second Amendment. For some, guns are a way of living. It is not until recently the Second Amendment has become a discussion topic. Through the interviews that our group conducted, I realized that it is a hard topic to pin down and this fact is a story within itself.

In many countries in the world, in Europe for example, the idea of having a gun is unnecessary. To a large extent, people do not own weapons. One cannot just buy guns as there are laws and restrictions that do not allow people to have them. In the United States, some people own guns while others are affected tragically on regular basis by them. There may be a mother that gets shot by her two years old child in Walmart, or a student who decides to take down a classroom one morning.

In The United States may be legal, however few people are willing to talk about their experiences and many do not even want to get into this topic.

It is interesting to also highlight that gun violence is also associated with police. Since the case of Trayvon Martin that sparked major media attention, there is a pattern of gun violence, and the phenomenon of how police officers deals with minorities and crimes. In many cases, they they often show up with guns in the hand, trigger happy and ready to shoot. This a what a lot of protest been about recently, the violence that comes from police officers. There are so many videos online that illustrate this rampage.

For example, Sonny is a 35 years old man who grew up in New Jersey, and he recalls a time during which police officers had a gun pointed next to his head for twenty minutes.

“They came out of the blue, patrolling, looking for guns, but they came with more guns.

”

Sonny is a victim of gun violence. He has been affected directly with the police and by losing family members like his nephew Radazz Hearns, a 14 year old who was shot 7 times by Trenton police officers in New Jersey on August 12, 2015. Apparently the teenager was shot because he pointed a gun at police officers who acted in self-protection, an shot him. However witnesses including Rhonda Tirado, who was sitting in front of her house when the horrific scene occurred, said that she saw the police get out of “unmarked gray minivan” where “three police officers got out to question the trio of teens.” Tirado says that she saw Radazz Hearns run away from police officers and this is when the gun fire started.

“I never heard of a personal story of someone protecting themselves with carrying gun in my personal experience…” says Florida native, Danny Waetes.

Police and gun violence go hand in hand in the United States. The story of young Radazz Hearns is not the first time that media spectators have heard one story according to the police and another story as told by witnesses or captured by smartphones, that proves to be contrary to what the police officers may have have said about the actions of shooting a victim.

Sonny, who grew up in New Jersey, says he is used to this routine of brutality. “One time I was in school - I got home. I got kids, we were hanging out in the neighborhood…they [the police] came out of the blue, patrolling, looking for guns, but they come with more guns.”

When asked what he thinks of owning guns, Sonny expressed that while he thinks that some people should be able to own guns because they need to protect themselves and family, he also explained how gun violence is “an irrational cycle,” because "there is an inequality... because certain groups of people are disproportionally affected by laws... for instance," he says, "lower class and black people have been incarcerated, and laws says they can’t own guns because they commit felony… some people just get guns because there is a need. This is a paradox which perpetuates the cycle of the incarceration.”

But what happens when gun violence leave the victims with trauma? Once someone is affected, this trauma can haunt them. Often for a lifetime.

Danny Waetes who is from Florida, was affected by gun violence 10 years ago, and was never was able to forget. He was with his partner when they were approached by three men with guns, who told them to get down on the ground, took their backpacks and sped off very quickly. “I never heard of a personal story of someone protecting themselves with carrying gun in my personal experience…”

Personally, he expresses that he “hates gun!”

Danny is an example among many people who think that gun should not be carried, and do not own guns.

by morgan young

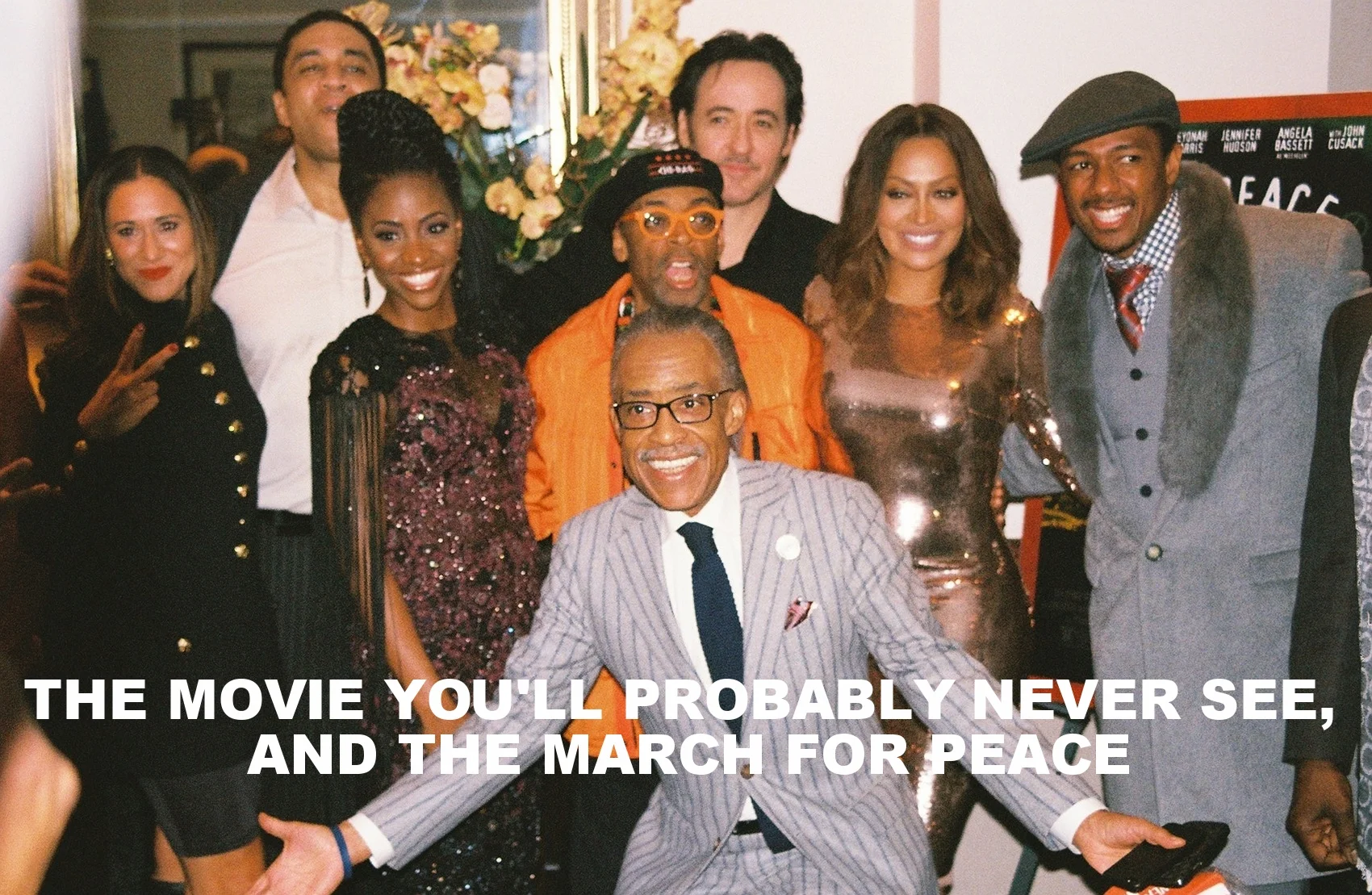

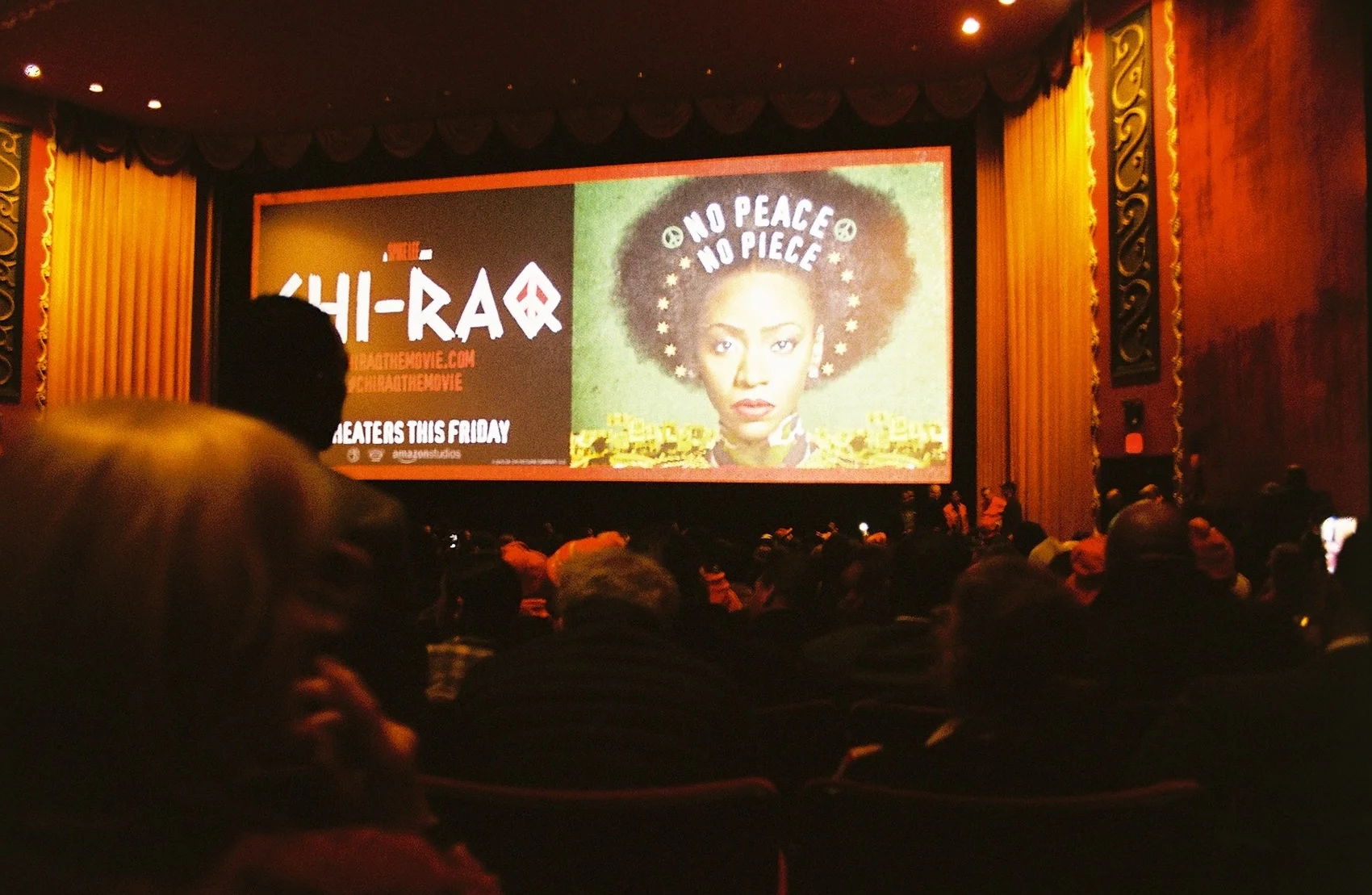

It’s under-publicized and playing in a grand total of zero theaters in most towns. Viewers will have to schlep to different boroughs to see it. Or, maybe, the only people who will try to see it live in those boroughs anyway. Chi-Raq. A Spike Lee Joint that’s not quite like the others. This modern day adaptation of Greek play Lysistrata is unexpectedly upbeat. It features gunshots, a war against the sexes, and a cast that will occasionally make viewers smile while demanding a call to action. There’s a message, of course, but it’s less subtle than the ones audiences received in Lee’s other films. Do the Right Thing ended in a Brooklyn war, with a pizza parlor on fire. Let that sink in for a minute. Lee has never been subtle. With Chi-Raq, the director plays no games - he does not hide his political sentiments, he does not skirt around issues. He simply draws audiences into a theater, turns out the lights and proceeds to scream. Save Chicago! He says. New York, L.A. Wherever being at the playground at the wrong time might mean seeing stray bullets graze a child. Wherever young black men are killing young black men. Wherever the police are helping them to do so.

Samuel L. Jackson, always suited up and wielding a cane, nails his role, breaking the fourth wall and making appearances as a narrator. “Chi-Raq, land of misery, pain and strife,” he says - in his Samuel L. Jackson way - walking jauntily toward the camera. Audiences will appreciate his direct addresses, but what could have made for a great movie is lost to what amounts to clownishness. Ridiculous attire on the women of the film, who chant, “no peace, no pussy” to their irate male counterparts, and too many attempts at clever prose. Lee is a Brooklynite, and what makes his other films golden, is his ability to capture the essence of his community. Anyone who has watched the director’s previous films can sense his unfamiliarity with Chicago. It would have been best too, if Lee forwent the earplug worthy rapping of Nick Cannon, in favor of - well - anything else.

This is a movie that people on Lee’s side of the argument will want to like, but the director - as talented as he is - could have made it easier for them do so. Is this a musical? Not sure. A satire? Almost. Comedy? There are several laugh worthy moments. Drama? Keep in mind the content. Those devotees who love Lee no matter what he does, will love this film. Those who support gun control will support its message. America needed a movie like this, so its limited release is disappointing. Viewers won’t get bored, but some will get lost. The message is great, but the presentation will fall flat for many.

Shanduke McPhatter, 36, began G.M.A.C.C after a year long stay at Rikers Island. (Photo Courtesy of Shanduke McPhatter)

by morgan young

Shanduke McPhatter has a dark office that is misleadingly large, a motley crew of young people who surround him, giving the place a colorful, familial spirit, and the presence of someone who should have considered going into film. He was born, raised, and is a resident of Brooklyn. The office of his company, Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Change (G.M.A.C.C.), sits across from a McDonalds on Church Ave, a Brooklyn street that remains lively even on rainy days.

McPhatter, a former member of the Bloods, is welcoming, though he has an intimidating air about him. He wears a heavy looking silver earring in each ear, and dressed in a black, fitted shirt adorned with shoulder pads, he looks almost militant.

It does not take long to notice that people listen when he talks. When asked what she was doing at G.M.A.C.C, one young woman gestured around the room and said, “We work here.” When asked for specifics, she said, “we do whatever Shanduke tells us to do.”

He is not a dictator, but a teacher. The environment feels less like follow the leader than it sounds, and instead demonstrates a mutual respect between McPhatter and the young people with whom he interacts.

The office feels like organized chaos, someone screams and McPhatter quickly straightens them out in a demanding, almost fatherly tone. The place is noisy, filled with interns, someone who runs PR, and a few friends. People come and go. Everyone seems to be doing their own thing, but they all respect the man in charge.

McPhatter was raised in and out of the foster care system, and grew up around - but never using - drugs, “without a want, or a desire to become anything.” He is familiar with the institution that is Rikers Island, and explains what a state bid is. This, McPhatter says, is a sentence of “anything over a year and a day.” It is referred to as going up North. “State prison," he says solemnly. "When someone gets convicted of a felony, they make that trip upstate.”

McPhatter made this trip to serve a state bid twice, but he has been to Rikers several more times than that. It was while he was in prison, that he realized he never wanted to go back. During this sentence, he saw the son of a friend become incarcerated. "The son was happy to be there. The father was just like wow, it’s because of me you’re here. Replicating a reputation. And I didn’t want that to be my story."

And so it wasn't.

He made a point of getting his life together. After they introduced him to fast money, crime and prison sentences, McPhatter might resent the Bloods, the gang that he was so involved with during that tempestuous time in his life. But McPhatter isn't anti-gang, he is simply anti-violence. He compares gangs to the fraternities and sororities that many young people pledge to upon entering college. But the fourteen, fifteen and sixteen year olds on the street? "They're too young and don't have all the necessary things around them - family, friends, whatever. No one wants to be alone. They become a part of something. Everything ain’t about crime."

“I’m overcoming being a black man, I’m overcoming being a convicted felon, now I have to overcome being categorized as a gang member. These things take away the value of my life. ”

He poses a question. "If I am a gang member and I don’t want to shoot anybody, I got a job and I’m taking care of my family, I’m not out there hurting anybody, and not committing any crimes, does it matter that I’m a gang member?" He pauses and shakes his head. "No. And that’s the difference, that’s what we focus on, people pay too much attention to what you’re a part of versus who you are and what you’re doing."

No matter how positive though, the negative affiliations that gangs have, can ruin lives.

"I’m overcoming being a black man, I’m overcoming being a convicted felon, now I have to overcome being categorized as a gang member. These things take away the value of my life."

But many young people feel they have nothing to live for. McPhatter tells a story of a young man who came into his office. "The guy said he was a part of a crew called the 90's. I asked him what his goal was," McPhatter shakes his head, "he said his goal was to be 'grimy.'"

While it is difficult to understand the drive to commit senseless acts of violence, to want to be 'grimy,' McPhatter says that people respect violence. "It’s true. When I say people respect violence, not everyone understands me. But if you come to the hood and you talk about being peaceful, they don’t care about that. When you punch somebody in they mouth, then everybody is... tuned in."

It's true, that in music, in movies, people are less interested in the nice guy than the villain.

“If you come to the hood and you talk about being peaceful, they don’t care about that. When you punch somebody in they mouth, then everybody is... tuned in.”

McPhatter's bottom line? Guns are a problem, but there's something even deeper. The community, and the happiness of the individuals that make it up. "If I have a good family, everything's going right in my life, I'm not walking around looking to shoot people. A good person with a gun ain't running around shooting people."

On the subject of the mass shootings that occur with alarming regularity, McPhatter says, "you've got these guys, allegedly teased and whatever. They snapped. But that's always when it's a white shooter. Let's keep it one hundred," he says, "you don't have young black men mass shooting places, The black man shoots the person he knows, who he grew up with. It's a different problem."

While there are so many more questions for McPhatter, he is polite, but too busy to continue. There's a "very important document" to be dealt with, "the guy upstairs" who wants to chat, and a ringing phone to be tended to. He's all out of time.